Human history and culture bear the unmistakeable impact of the separation and recombination of distinct groups of people. In this week’s post I will explore, from past to present to future, notable examples of the hybridisation of humanity.

The most recent genetic analysis reconstructed a hybrid origin for Homo sapiens themselves, long before they left Africa.

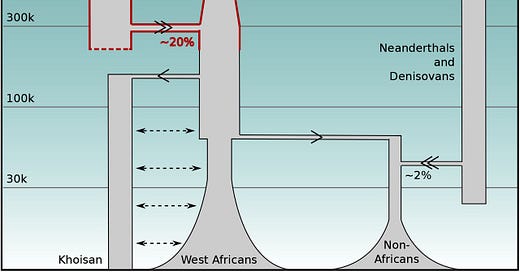

The main human lineage split around 1.7 million years ago (with one branch giving rise to the Neanderthals and Denisovans, more on them later). The split lineage that remained in Africa recombined around 300 thousand years ago, producing Homo sapiens. The Khoisan people of south Africa split from this founding population around 100 thousand years ago, with the rest of humanity branching off to make up the majority of people alive today.

As Homo sapiens spread out of Africa around 60 thousand years ago they encountered Neanderthals in the Middle East and Europe, then various Denisovan groups throughout Asia. In multiple instances hybridisation between these widely diverged groups took place, providing the tropical Homo sapiens with a range of adaptations to colder and high altitude environments that the Neanderthals and Denisovans had long adapted to. This crossing over left a trace of a few percent of the DNA in modern humans, rising as high as 5% Denisovan in Papuans. The people who remained in Africa interbred with an unnamed ancestral species, leaving 2-19% of their DNA in modern Africans.

This pattern of splitting and recombination continued through more recent history. The people of India are predominantly descended from a mix of Dravidians (whose ancestors first left Africa along the coastal route 60 thousand years ago) with horse riding Yamnaya who arrived from the north 4 thousand years ago. This combination produced the equivalent of a radiative speciation, with various combinations of influence frozen in time through the caste system until modern times. A gradient in the contribution of the two peoples remains, with higher Dravidian influence further south. At the extreme, the isolated people in the Andaman Islands represent a pocket of people virtually untouched since that original Homo sapiens migration out of Africa.

Another fascinating example is found in the people of Japan. For up to thirty thousand years Japan was populated by the Jomon people, who displayed a host of features more typical of modern Europeans. Around ten thousand years ago rice farming east Asian people arrived from the Korean peninsula. They rapidly spread, but interbred with the Jomon foragers, so around 10-20% of the DNA of modern Japanese comes from the older Jomon people. In the far north, where rice is harder to grow, as well as isolated islands such as Okinawa, the percentage of Jomon heritage is often as high as 30%. Small tribes of Ainu people trace as much as 70% of their ancestry to the Jomon.

The most recent and extreme example of this phenomenon has been discovered in the origins of the Polynesians. Their ancestry has been traced to a small group of Austronesian sailors who left Taiwan around 4 thousand years ago. They sailed south until they reached Papua, where they were joined by a small group of Papuan women. Their journey then continued on into the Pacific, where they successively settled every habitable island in that vast expanse of empty, hostile ocean in what was the last major migration of humanity across the planet.

The industrial era has seen people moved across the planet and mixed up in combinations that were previously unimaginable. Several areas stand out as being exceptional in this regard, and they may prove to be origins of entirely new peoples and cultures in coming centuries. In East Asia, the Philippines stands out as the most interesting, with around 5% of their genetics coming from Europeans, with the remainder being evenly split between ancient Austronesian and more recent mainland East Asian contributions.

All of central and south America features varying mixtures of founding people, though Mexico stands out as a noteworthy example with a fairly even blend of indigenous and European ancestry, with a significant contribution from Africa. Africa itself also features a few pockets of unusual blending. Cape Verde has a large population with a mix of Portuguese and African heritage.

South Africa has around five million people in their “coloured” population who represent a complex mixture of 25-40% Khoisan and 15-35% Bantu African, 20-40% European and 10-20% Asian. The Khoisan contribution is especially notable since this very early branch of Homo sapiens retained vastly more genetic diversity than the small populations who left Africa. This final group is probably the most genetically diverse population of humans on the planet today, and as such may represent the founding population for a radically divergent branch of humanity in time. The comedian Trevor Noah is a well-known individual from this people.

The trends for interracial marriage around the world are generally creeping upwards over time. In the USA interracial marriages reached 20% of new marriages 2019 after being legalized nationwide in 1967. With current trends the USA would become majority multiracial by around 2075. Black interracial marriage is less common so the black identity is likely to persist the longest.

Of course, current trends are unlikely to remain unchanged as we move through what is likely to be a turbulent 21st century. Past mixing of distinct peoples usually originated from massive migrations in response to major pressures. Not that long ago, our scientific institutions were obsessed with the negative effects of “miscegenation” which supposedly threatened the “purity” of races thrown together in the industrial age.

I wonder if the pendulum will ever swing in the opposite direction, and that some unusual group of people could make the blending of distinct people into a corner stone of their founding identity. The Polynesians demonstrated the enormous power of this pathway. Such a determined group could emerge victorious from the wreckage of the Industrial era, to explore the vast empty oceans of time that awaits our many and varied descendants.

It’s interesting to me that essentially a whole new ‘race’ of people (Polynesians) was made by just 1 cross between two different groups, and with what was probably a pretty small starting population. Probably a lot more genetic diversity in and between the founding groups than today, but still makes one wonder at what brand new combinations are waiting to happen in the near future.

Wow! I was determined to NOT get distracted by email, but you lured me in, entertained, and most importantly, enlightened. As a sort of Irish Catholic mutt from New England, which is a lot like the old England, I'm fascinated by the ability of science to sort our genetic heritage(s). (and I'm using this in my writing)